IN BURYATIA, THEY COOK DELICIOUS FOOD, PLAY DICE, AND BELIEVE THAT THE KNOWLEDGE OF A PAST LIFE CAN BE REMEMBERED. THEY ARE ALSO ENGAGED IN A NON-STOP STRUGGLE FOR SURVIVAL — A STRUGGLE JUST AS FIERCE AS IT WAS CENTURIES AGO. OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT GRIGORI KUBATYAN TRAVELLED TO THE REPUBLIC TO SEE THE WINTER BAIKAL WITH HIS OWN EYES.

We are sitting in a restaurant-yurt (a large type of tent unique to central Asia). It has eight walls, a heater in the middle, portraits of Genghis Khan on one of the walls, and stand-up comedy on TV. A wooden toono wheel hangs under the ceiling. It doesn’t perform any useful functions, but its spokes symbolically unite the different parts of the yurt into a single space. A waitress brings us steaming hot buuz — perhaps the best-known Buryat national dish.

Buuz and Poza

The buuz, or poza as they are also known, aren’t merely a traditional dish and the republic’s main gastronomic attraction. They are an essential part in the celebrations of all the significant events in the lives of Mongolian people. Buuz have had poems dedicated to them, been celebrated with festivals, and been honoured by a national anthem of their own, by a monument, and by an annual prize initiated by the Ulan-Ode restaurant association — not to mention revered by an army of fans all over the world.

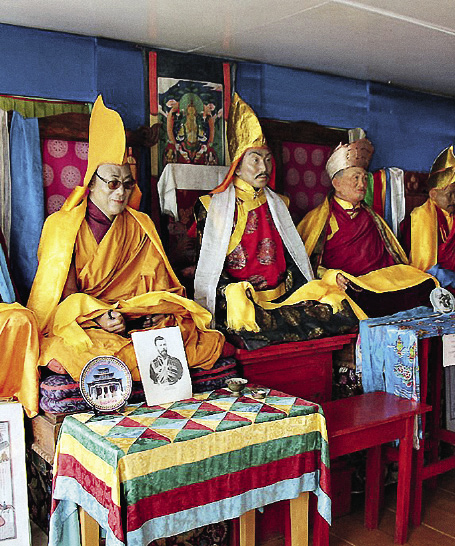

Empress Elizabeth was the fi rst ruler to approve

Buddhism in Russia, thus earning herself the

status of the incarnation of the goddess of wisdom

Hot buuz are similar to khinkali, only without tails. But you eat them the same way — by picking them up with your fingers, gently biting one of the warm sides and sucking out the aromatic broth, and only then gnawing into the hot pulp.

Bowls of salamat are placed in front of us. Salamat is sour cream whipped with flour. It’s very filling, although perhaps an acquired taste. As it happened, not everyone at our table relished it, although I certainly did.

“Eat some salamat and you won’t feel hungry until the evening,” explains Darima. “Sometimes it is served to guests at wedding banquets before the main courses in order to save money on food. This makes perfect sense. Our traditional weddings usually have about 400, or even 600 guests — not every family can afford to feed so many!”

How Medvedev Became The White Tara

The morning sun is low. Smoke rises over the single-story houses.

We’re on our way to the Ivolginsky Datsan, the most important monastery of the Buryat Buddhists. The Buryat Buddhist tradition is part of the wider Gelug (meaning Yellow Hat) tradition within Buddhism. The tradition’s leader, the Dalai Lama, lives in India. His deputy in Buryatia, the Khambo-Lama Damba Aysheev lives at the datsan.

The head of the Buddhist community is very active. One day he will distribute the so-called “social flocks” to the poor, the next, donate three hundred sheep to the Archery Federation, and yet the next, arrange a sheepskin dressing contest. The datsan has a sheepskin processing shop of its own. The stadium where local sporting heroes compete is there too.

At the yurt you will be invited to join a “yokhor” round dance or to play a game of dice. The bones of the dice stand for one the “Big Five” animals. Which one you get is decided by how the dice fall to the board. If they fall on their side, it’s a cow or a sheep.

It is believed that Buddhism in Russia was first allowed by Empress Elizabeth, for which the East Siberian Buddhists declared her to be the embodiment of the White Tara, the goddess of purity and wisdom. Then this title was inherited by Catherine the Great. And, in 2009, when the then President of the Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev came to Buryatia, and visited the datsan, he too was proclaimed the White Tara. Mr. Medvedev didn’t seem to mind.

“Why wasn’t Putin proclaimed the White Tara as well?” I asked at the datsan.

“Once we had offered this title to Medvedev, we felt it wouldn’t be very polite to offer the same to Putin,” was the somewhat regretful reply.

The Ivolginsky Datsan looks like a Russian village with its cabins, window shutters, and chimneys. The front doors of the cabins are guarded by statues of Chinese lions, while large, bright pagodas are scattered everywhere.

The datsan has several functioning temples. Monks spend their time chanting prayers, banging the gongs, or blowing into large seashells, an act which symbolizes the victory of knowledge over ignorance.

The Past Lives of the Buryat Lamas

One of the pagodas belongs to Khambo-Lama Itigelov, who served as the head of Russia’s Buddhists before the revolution. Itigelov was buried in a cedar box, sitting in the pose of the lotus, but his body is believed to have remained intact. A sort of mausoleum has been arranged in his pagoda, with the body exposed behind a glass pane. In front of the glass pane stand vases with food offerings. Sometimes the cat that lives in the mausoleum comes and takes a bite of the offerings — the monks on duty at the pagoda have nothing against this.

You can make the Khambo-Lama a gift of a blue ceremonial scarf, or khadak, by placing it on the box next to him, and then taking another one with a blessed knot.

Previously, the khadak was not a scarf, but a belt into which you could tuck weapons. If a nomad took off his belt and gave it to someone, it was a token of friendliness and sincerity, like an open hand. You cannot hide a knife in an open belt, after all.

At the datsan, prayer drums begin to spin and incense is being burned, as the small, multicoloured flags known as “khee morin” (meaning “the horses of the wind”) flutter in the wind. The forest beyond the fence is filled with such flags. I was told that lamas were buried there in the past.

The Ivolginsky Datsan is located to the east of Ulan-Ude, with the Atsagatsky Datsan located to the west of the capital. While the first monastery looks lively, even festive, the second one is full of reflection. Before the war, it housed a Tibetan medical institution, and then an orphanage based on a juvenile colony. The 1990s saw the beginning of the datsan’s restoration, and the Dalai Lama came there to personally bless its revival. Today, in addition to being a monastery, it is also an academy.

“We study Buddhist philosophy, astrology, medicine, secret sciences, and art,” says the 62-year-old rector of the datsan, Tarba Dorzhiev. “It will take a student 20 years to study even one of these disciplines. A lifetime would not suffice to study them all. Fortunately, we have begun learning a lot of it in our past lives.”

“So, you’re not learning, you’re remembering, correct?” I ask.

“Yes, that’s correct. I’m remembering,” the rector agrees.

Calendar of Events

ICE MARCH

AT THE END OF MARCH, BAIKAL SEES THE “BAIKAL ICE MARCH”, A RE-ENACTMENT OF RUSSIAN TROOPS’ MARCH ACROSS THE LAKE IN 1904-1905.

FISHING UNDER THE ICE

SPRING WOULD NOT BE COMPLETE WITHOUT THE POPULAR ICE FISHING CHAMPIONSHIP NAMED “BAIKALSKAYA KAMCHATKA”.

DOG RACES

ONE OF THE MAIN EVENTS OF THE WINTER CONTEST “ZIMNIADA” IS THE DOG SLED RACE, THE “BAIKAL RACE” OVER 56- AND 155-KILOMETRE DISTANCES.

THE YORD GAMES

THE ETHNO-CULTURAL FESTIVAL “THE YORD GAMES” IS HELD IN JUNE BY THE MOUNTAIN OF YOKHE YORD.

MUSIC FESTIVAL

THE “BAIKAL JAZZ” MUSIC FESTIVAL HELD IN APRIL FEATURES CONCERTS BY RENOWNED JAZZ MASTERS.

THE BAIKAL MARATHON

THE BAIKAL ICE MARATHON, WHICH WILL BE HELD FOR THE 18TH TIME THIS YEAR, IS ONE OF THE WORLD’S TOP FIVE ENDURANCE RACES.

Throw the Dice and Win a Horse

The sculptural group located opposite the datsan depicts a horse, a bull, a goat, a sheep and a camel — the Buryat “Big Five” of the animals that provide sustenance for the nomad.

The “Nomad of the Steppes” complex is located nearby. In summer, it houses a large number of folk music festivals. The winter season, however, has other attractions. You can take a sleigh ride, give a camel a pet, and try your luck at shooting with a bow and arrow. Inside the yurt the round dance — the yokhor — is often performed, and you’re always welcome to join in, unless you choose to play dice instead.

The dice used in Buryatia are made of real bone. They play two types of games — trials of strength and board games. To demonstrate your strength, you need to firmly grip a ram’s backbone, take a swing, and hit it with your fist as hard as you can. This is very likely to hurt your fist, but there are experienced masters who can split dozens of such bones in a contest. The stakes are quite high — apartments and cars, for example.

In the board games, lamb vertebrae that symbolise the animals of the “Big Five” are used — which one you get depends on how your dice fall on the field. If a bone lands on its side, you get a cow or a sheep. If it stands upright, then a camel. Ideally, you need to throw your dice in a way that will get you a horse. Then you can move the bone to the next mark.

Among them are ice grottoes, lakeside cliffs covered in wondrous icicles, and these fantastically beautiful methane bubbles.

A stove stands in the centre of the yurt, making for a warm and cosy interior. The most feared curse among the nomads is: “may the fire die in your hearth.” The best wishes you can give someone, then, must be: “may the fire in your hearth never go out.”

Where Did the Omul Barrel Go?

The wind is blowing over the vast steppe outside. Mountains are silhouetted in the distance. We are continuing our journey onwards, to Lake Baikal. On the way, we stop by all the places where spirits live to sprinkle them with alcohol. It’s no bother for us, and it keeps the spirits happy.

In the past, the Trans-Baikal mountains were home to gold mines worked by convict-labourers. Sometimes the convicts working there managed to escape. They travelled on foot through mountains and forests, homeward to the west. Between them and home, however, lay a giant, sea-sized lake.

The songs from those times are at once sad and frightening. One such song is “Over the Trans-Baikal steppes.” Its lyrics go like this: “A weary wanderer takes a boat to cross Lake Baikal alone, and under his breath he hums a sorrowful tune, a song of returning home.” These words seem to express a glow of hope of deliverance and a happy life. But as the song goes on we learn that the wanderer is to be met with sad news once he crosses Baikal: “Your father’s long-since cold in his grave, your brother’s long been bound in shackles.”

Another well-known song is “You, glorious sea, o blessed Baikal; an omul barrel is a good vessel.” It has been performed by many — a choir of convicts, the Ministry of Internal Affairs ensemble, and the Russian musician Boris Grebenshchikov. In the latter’s interpretation the protagonist seems to be sailing on his boat somewhere in Ireland. The song talks about how the runaway couldn’t find a boat, so he ventures across the endless lake an empty omul barrel (an omul, by the way is a type of fish found only in Lake Baikal). In the original version he is sailing for four days, and it is unclear whether he will make it or perish.

“He must have set sail from here, where Cape Svyatoy Nos makes a deep curve. The mountains and taiga were perfect for hiding from the gendarmes. The wind and the current would have carried the barrel to the opposite bank, so he had a chance,” explains Sergei Volkov who works at the United Directorate of the Barguzin State.

In Soviet times, work and electrical power were provided by fish factories on Lake Baikal. Today the factories are closed and their fishing vessels lie helplessly on the shore like whales washed up by the waves

Natural Biosphere Reserve and the Trans-Baikal National Park. Nothing like this would work these days. The State Inspectorate for Small Vessels wouldn’t have an unclaimed barrel floating about without permission.

You won’t find an empty omul barrel on Baikal’s banks either. Commercial omul fishing has long been prohibited. One can still catch it for their own household, but not more than 5kg per person. If you’re lucky, you can still taste omul soup made by village fishermen, but you can’t buy any in the city. If you ask about it in a shop, the staff will look at you in terror, as if you’re asking for cocaine.

A Race for Survival

The road is frozen over and the reserve’s UAZ-452 (popularly known as “breadloaf”, due to its shape) is running smoothly and at a good speed. Almost all the land around Baikal is a nature reserve or a national park. That’s good for the environment, but not so good for the people who live here. For centuries they have been fishing in the lake and cutting down trees in the forest, but now these traditional activities and others have been outlawed.

“They are labelled poachers, but it is not they who came to the national reserve area, it was the national reserve that came to them,” Volkov explains. “There aren’t any other jobs. What means do people have of earning their living? Tourism development is being encouraged, but how can tourism be developed when building is forbidden on the reserve territory? There’s no way of opening a hotel, a restaurant, or a store. You can’t get electrical power or build sewage treatment plants. Approval of any works on the reserve territory is very costly. Infrastructure needs to be in place before the status of a reserve is assigned to an area. Afterwards it isn’t possible to build anything, nor even link up to the water mains.

In Soviet times, work and electrical power were provided by fish factories located on Lake Baikal. Today, the factories are closed and their fishing vessels lie helplessly on the shore like whales washed up by the waves. The village houses are equipped with solar panels, to which they have turned out of despair rather than from any wish to maintain an eco-friendly lifestyle. Other energy sources are non-existent.

“It’s pointless to wait for the omul to multiply,” says Sergei Volkov. “We need to stock the lake. This was done in the past, but not today. If the omul is plentiful, the fishing and the processing will come back. The people wait and hope.”

Baikal freezes over in winter. There are several fishing camp-sites on the lake. They offer accommodation in yurts complete with stoves and beds, located right on the ice. There are holes cut in the icy floor. You can rent a yurt like that for a few days and wait for a bite. But it won’t be cheap —

renting a yurt costs 1,000 rubles (about $13) per person per day. Your catch would have to be literally gold-fish to justify that!

There’s a motorway that leads right over the ice. You will see speed limit signs as low as “10”, but in reality, the traffic moves at highway speeds. The ice is smooth and hard. Even car races are held on Lake Baikal, similar to those in the American state of Utah. The racers at the “Baikal Mile” reach speeds of up to 250 kilometres per hour.

In summer, yacht regattas are held on Lake Baikal, while popular winter activities include ice hockey and ice golf, skiing and riding snowmobiles. When not covered in snow, the surface of the frozen lake looks like glass. The grottoes of Baikal’s islets are adorned with incredibly long icicles.

The area of frozen lake by the village of Maksimikha has been turned into a skating rink. Skate rental is available at the nearby tourist base for anyone willing to try out the ice. It’s right in the middle of the lake, with mountains all around, and such beautiful sunsets!

“This is so lovely,” I exclaim.

“It is,” agrees the owner of the tourist base, Anna Maslichenko. “But if someone offered me money, I would sell everything and leave at once. All the coastal sawmills stand empty since December. We’re not allowed to use coal for heating, we’re out of firewood, and electricity is expensive. We have installed solar panels, but they are useless. Our future here is uncertain.

We want to believe the best. We want to believe that the government will start guarding the interests not only of nature, but also of those living in it. To guard in the good sense of the word, not in the way that makes people want to set sail across the lake in a barrel.”

PHOTO: ALBERT-MOTSAR.LIVEJOURNAL.COM / AUTOPLUSTV.RU / BAIKAL-BURO.RU / DREAMSTIME / INSIBERIA.COM /

JASSOTOUR.RU / NFPOL.RU / ANNA OGORODNIK / GRIGORY KUBATYAN / MIKE KATALOV / MIKE LEUNG / MARINA DYACHENKO